What freedom brings

Azeeb’s wife, Shagufta, places a garland of flowers around my neck at the entrance to their home, and the children throw flower pedals at me—directly in my face, as is the custom, I guess—giddy with smiles. If I’m honest, it was embarrassing and humbling at the same time. I’m just a messenger, I thought, representing so many others who’ve given, prayed and worked to make this moment possible. Why should I get all the love? But soon I push back my reservations and embrace the moment—enjoying the smiles, the hugs, the laughs with the children and, of course, more tea.

Azeeb wraps his arm around my shoulder. “When we found out you were going to pay off our debt, we were thrilled. My wife said she’d put her hands on your head [a sign of honor that elders give to the younger], regardless of your age!” he laughs. “We stayed up until 1 a.m. last evening talking and discussing this day. We couldn’t sleep we were so excited,” he says.

It’s too hot to stand outside for long so we walk into his bedroom and crowd around the bed, sitting in white plastic chairs, sipping chai and talking. “My whole family, my sons and my daughters have all said that you are on their hearts,” Azeeb says.

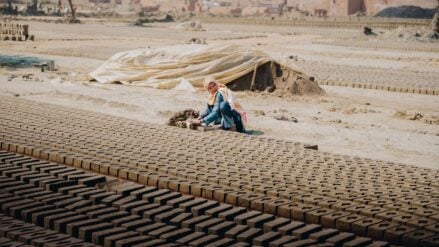

At many points in our conversation, I’m speechless. How do you commemorate this moment? What words do you say to someone who has regained their freedom. Azeeb and his family have been at this brick kiln for almost 25 years and most of it has been in bonded slavery.

When I ask Azeeb how it feels, he says, “God sent us angels to bless us, and now we are free.”

“Your visit here reminds me of the story of Moses,” Azeeb adds. “God sent Moses to release His people from bondage. God is working for us, and He can save us. He can protect us. I prayed for freedom and God answered.”

It’s amazing to be a part of this answered prayer, nearly 25 years in the making. The cosmic plan of God is hard to wrap my mind around. Twenty-five years ago, I was in seminary studying theology in Phoenix, Arizona, while Azeeb was here in Lahore starting his time in the brick kilns. Neither of us would’ve ever known or imagined what God had in store for us in a quarter century right here, outside Lahore.

At one point, Azeeb becomes more serious. “I would like to thank all those who gave generously and prayed for us. Bless you all from the bottom of my heart,” Azeeb says.

It’s hard to leave Azeeb and his family. Shugufta gives me a big hug and the children pass along high-fives and more smiles.

“We are all deep friends in Jesus,” Azeeb says. And my heart is full.

On the way home to the US again, my mind wanders. How many other persecuted Christians have been praying for freedom across Pakistan’s brick kilns? How many other families are asking God to break the cycle and free the next generation?

That’s when I know our work here is just beginning.

Will you take a moment now and pray with us, reaching out to God on behalf of the other persecuted brick kiln workers?

Father God, You have a plan. You intertwine lives and bring opportunities. We’re grateful for the generous support of our donors, that we were able to free these families from bonded slavery. But we know others remain. Please encourage them and bring them peace. Let them feel Your presence and keep their hopes high. And if it be Your will, free them, like the Israelites from the Egyptians. Amen.

About the author

Brian O. is the Chief Global Story Officer for GCR and partners with the persecuted church around the world to make sure their stories are heard. Get the latest stories and prayer requests at GlobalChristianRelief.org.