Their home, situated just beyond the view of the tall chimney from the kiln, is a small enclave with four rooms and a wide, uncovered porch. The open patio is for family meals and for animals: goats, calves and chickens. We sit for tea and to hear more about their story and faith. Their children and grandchildren scooch in close to listen to our conversation.

Trapped in the kilns

“The process of making bricks is a big challenge as it’s very heavy to transfer the clay through a handcart into the brick kiln,” Sayad says.

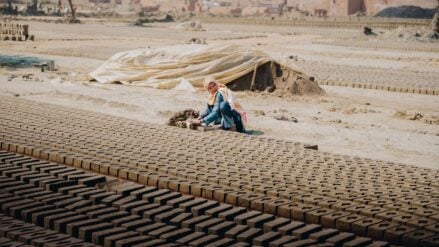

For many brick kiln workers in Pakistan, this is part of everyday life—preparing the clay, carting the clay to the flats and shaping it into rows and rows of bricks ready for baking. It often starts at 4 a.m. The daily brick quota can range from 1,500 to 2,500 bricks per family.

Sayad and Ruth started working in the kilns shortly after they were married and had children. As they expanded their family, costs quickly began to rise, and what they made for a living didn’t provide enough to support their children. That’s when they took their first loan—over fifty years ago.

But working in the kilns isn’t an ordinary job. It’s a form of slavery.