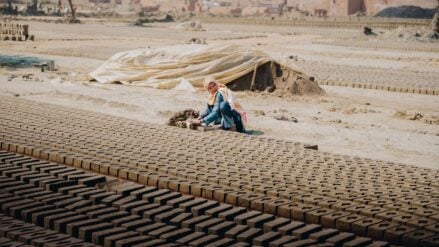

As we walk through the brick kiln factory, we see walls of bricks surrounding a kiln that reaches high to the sky and flows with smoke. We see men at the top of the kiln stoking the hot fires with coal. They wear wooden shoes because the temperature in the summer would melt rubber soles. Beyond the kiln, we see an assembly line of families on the flats. A few members make the mud and use a rickety wheelbarrow to bring it to the brick makers, who crouch, knees fully bent. There’s a rhythm to their workflow that’s almost like music.

Grab mud and place it in the mold. Pinch more mud from the pile and slap it on top. Flatten it. Pat it at the corners. Flip it. Pull the mold and start another. When they’ve finished a line of bricks, row after row, with the insignia of the brick kiln owner, lay in the sun until they’re ready to move—either to store or to bake.

For many brick kiln workers and persecuted Christians in Pakistan, this is part of everyday life. It often starts at 4 a.m. The daily brick quota can range from 1,500 to 2,500 bricks per family.

But there’s more to the story.